As the planet continues to warm and humans encroach on more wilderness areas, scientists warn of the unfolding sixth mass extinction on the planet. To evaluate the progression of this catastrophe, researchers need a large amount of high-quality data that contains detailed records of plant and animal biodiversity across the planet. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) provides the largest open-access biodiversity data network for researchers, conservation agencies, and ultimately, policy makers. It also provides a bridge to organizations, like museums and citizen science groups, that hold valuable biodiversity resources. With all of this information, could GBIF provide researchers the resources they need to slow the threat of the next mass extinction?

Venturing into the Jungle of Data Science

For centuries, museums have held the storehouse of specimens required to understand biodiversity across the planet. These archives serve as historical snapshots of biodiversity in one area, at one time. This information, until recently, has remained isolated. Recent efforts to digitize collections has produced a bridge between these rich troves, combining collections into a larger pool that researchers can tap to tackle bigger questions about global biodiversity.

“Datasets from thousands of museums across the globe are increasingly digitized and accessible in publicly searchable, online data portals,” said Mason Heberling, assistant curator of botany, co-chair of collections at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and first author on the study. “We are increasingly swimming in high volumes of data, but accessing and making sense of these data can be the limiting challenge.”

Big data is big, too big for one person to pour over in their spare time. Like any great exploration into the unknown, Heberling consulted with some experts. In this case, he popped over for a chat with folks at the Digital Sciences, Humanities, Arts: Research and Publishing (dSHARP) coalition at Carnegie Mellon University. Their conversation crystalized on an approach to unearth the secrets hidden in the datasets. These early conversations continued, grew into a collaboration and resulted in a paper published in the February issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is a great example of how digital humanities can collaborate with the sciences,” said study co-author Scott Weingart, program director for the Digital Humanities at CMU. “Often times a collection is based on a particular place, time, or taxa. This [database aggregates] all of the information together so biodiversity science can make broader and more global claims.”

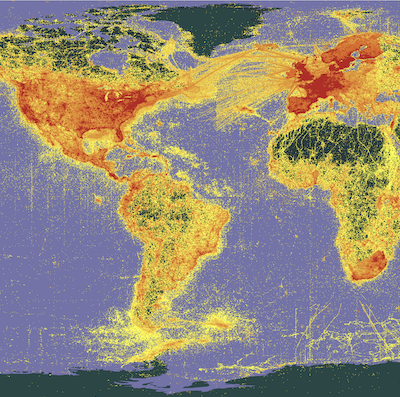

Image: Map illustrating more than 1.5 billion digital records of species occurrences, freely and openly accessible through the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Credit: OpenStreetMap contributors, OpenMapTiles, GBIF

Read the full article on the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences News page.