At the National Gallery of Art Datathon, held on October 25, a team of CMU researchers used computer vision to bring several related, but scattered, collections together in order to visualize the artistic preferences of two major art collectors and the resulting impact on our nation’s premier public art museum.

The Datathon marked the first time an American art museum had invited teams of data scientists and art historians to analyze, contextualize, and visualize its permanent collection data. The Gallery released its full permanent collection data to six teams of researchers, with instructions to pursue whichever avenues of inquiry they found most compelling.

Participating researchers came from universities including Bennington College, Carnegie Mellon University, Duke University, George Mason University, Macalester College, New College of Florida, University of California, Los Angeles, and Williams College.

The joint team from CMU and the University of Pittsburgh included Digital Humanities Developer Matt Lincoln, Golan Levin and Lingdong Huang of the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, as well as Sarah Reiff Conell of the University of Pittsburgh Department of History of Art and Architecture.

Understanding provenance, or the history of how an artwork has moved between owners since it was created, is vital for art historians to paint a complete picture of the history of an artwork’s impact on the world. Collectors may choose to acquire an artwork for many different reasons. While some have a very specific visual taste, others may be driven by interest in a specific period or artist, caring much less about whether an artwork uses a certain palette or style. With the technical know-how of Golan and Lingdong, and the art historical expertise of Matt and Sarah, the team had the opportunity to compare historic collectors’ choices to the visual traits of tens of thousands of artworks, and visualize the impact of those choices on the National Gallery’s collections.

In the early twentieth century, philanthropists Samuel H. Kress and Lessing J. Rosenwald each bequeathed major portions of their collections to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Kress’ paintings formed the backbone of the National Gallery’s European paintings, and Rosenwald’s enormous graphic arts collection became the foundation of the Gallery’s Old Master prints and drawings department.

However, only portions of their collections went to the Gallery. The rest were disseminated across other American institutions, with much of Rosenwald’s going to the Library of Congress, and Kress’ collections to nearly 100 regional and university museums across the country.

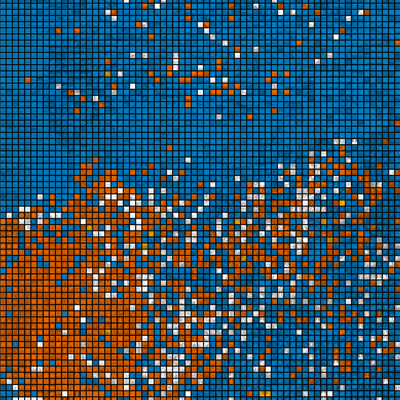

By running images of over 90,000 artworks through a neural network, the CMU team created visualizations of the entire collection that grouped artworks based on their visual similarity. For example, landscapes tended to sort with other landscapes and portraits were sorted with other portraits.

By overlaying curatorial metadata onto these visuals, using their computer vision pipeline, the team revealed, at scale, the artistic preferences of Kress and Rosenwald, and how those preferences shaped the art historical narrative that the National Gallery of Art presents to its visitors.

“For example, visualizing Kress’ collecting patterns, we could see that even though Kress’s larger collection was strongly inclined towards religious works and portrait paintings from Italian Renaissance, his bequest to the National Gallery was quite diverse,” said Lincoln. “It included not only figurative works, but also a large portion of the few landscapes and still lifes he’d collected.”

The Datathon project is an example of using cultural heritage collections as data, allowing the researchers to ask questions that would be difficult or impossible to answer by looking at one object at a time. These data science methods are also critical to bringing together curatorial data from collections that are otherwise siloed in different institutions.

“Computer vision combined with good curatorial metadata creates new opportunities for making serendipitous connections between works that might not traditionally get displayed together in an exhibition,” said Lincoln. “As a result, enthusiasts can get a chance to virtually stumble across artworks rarely exhibited to the public, while scholarly researchers gain more tools for searching vast image collections and finding previously-unknown visual links.”

A Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon held at the Gallery on Saturday, November 16, 2019, extended these efforts—encouraging participants to focus on prints and drawings and make use of the images of more than 22,000 works on paper from the Gallery's collection that will be donated to Wikimedia Commons. With these efforts, the Gallery continues its commitment to encouraging public engagement with its collection through open cultural heritage efforts.

Top and bottom image: Visualizations presenting the paintings from the Kress Collection and the National Gallery of Art. Learn more about these images and view more visualizations from this project.