This November is the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, the end of World War I. To mark the occasion, I thought I would dig into the early history of the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research to highlight some of the work that was carried out there during World War I.

Established in 1913, the Mellon Institute was roughly a year old when war broke out in Europe in 1914. That same year, its founder Robert Kennedy Duncan passed away at the age of 45, never to see his concept of the industrial research fellowship system flourish into a pioneering industrial research firm.

By the time the United States became involved in World War I in 1917, scientists at the Mellon Institute had already been contributing to the war effort for several years. The Robert Kennedy Duncan Club, the Institute's social club, organized numerous lectures by leading experts to familiarize the fellows with technical and chemical aspects of warfare. Previous research conducted in refractory materials, heat insulation, fuel conservation, and low distillation coals proved to be applicable to pressing war problems. Scientists were also engaged to seek out substitutes for Glycerin and Acetone, which had become scarce, and asked to review materials that were being considered for purchase and suggest improvements wherever possible.

The First Charcoal Gas Mask

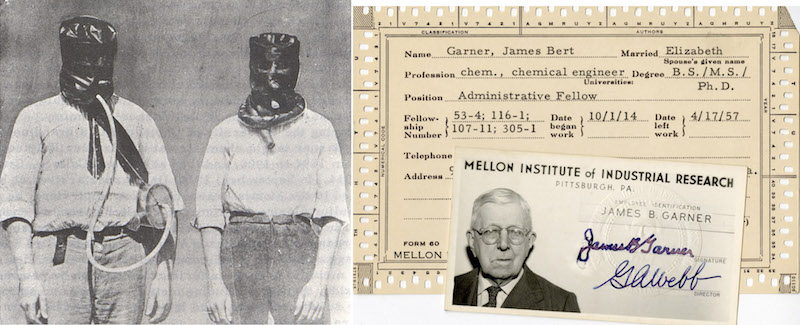

(left to right) Clinton Clark and Howard Clayton, shortly after the memorable test of James B. Garner's gas mask in 1915; Dr. James B. Garner's Mellon Institute ID card and personnel record.

WWI proved to be a very deadly war. High causalities were partly due to new technical and industrial advances, including the use of gas. On April 22, 1915, during the Battle of Ypres, the first mass use of poison gas was used by the German army. After reading about the attack on French and Canadian's troops, Dr. James B. Garner, a chemist at the Mellon Institute, began developing a more effective respiratory mask using charcoal to purify the air. Dr. Garner received enthusiastic support for his idea by Dr. Raymond Bacon, who was director of the Mellon Institute at the time. Together with his wife Glenna Garner, Dr. Garner created two masks from oil linen cloth.

According to a 1953 article on Dr. Garner in the Mellon Institute Newsletter, 'One contained a canister filled with pellets of prepared wood charcoal, while the other was a tube type which contained the charcoal in a large cloth tube attached to the mask. These two masks were then tested in a laboratory at Mellon Institute by two men, Howard D. Clayton, Dr. Garner's assistant, and Clinton W. Clark.' The masks worked, both men were able to breathe normally for over a half-hour before they began to notice the first odor of chlorine gas. Additional prototypes were created and sent to the British government for additional testing, before being mass produced in England and the United States.

Because poisonous gases were being used, gas research and development became part of the Chemical Warfare Section of the U.S. Army and Dr. Raymond Bacon, the director of Mellon Institute, and Dr. William A. Hamor, the assistant director, were sent to France to advise the army.

Once a Fellow Always a Fellow

In addition to Dr. Hamor and Dr. Bacon, 29 fellows from the Mellon Institute enlisted into the army within the first year. Fellows who remained in Pittsburgh were assigned to special research problems by National Research Council. Vacancies left by those who enlisted were filled in most cases, but given the shortage of skilled men, the Institute was forced to temporarily suspend a handful of fellowships.

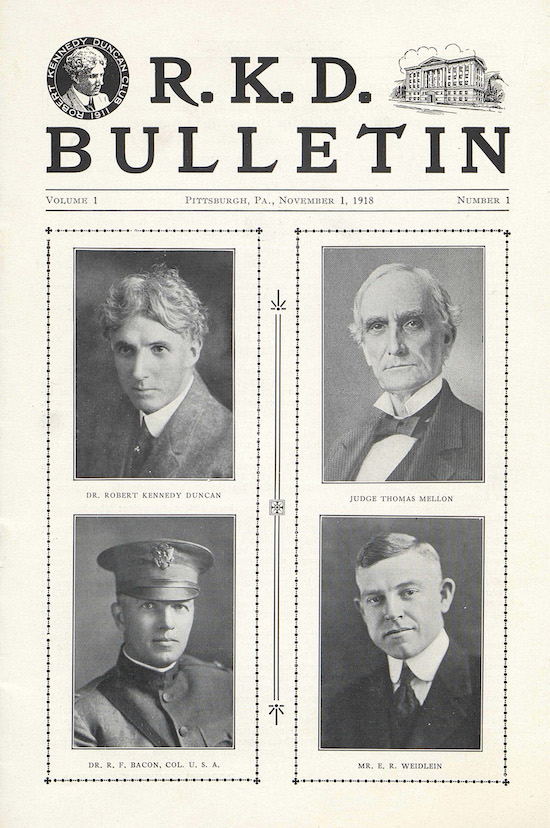

In 1918 members of the Robert Kennedy Duncan Club starting publishing a newsletter called the R.K.D. Club Bulletin. Taking inspiration from Duncan, the Institute's founder, who said, 'Once a fellow, always a fellow', members used the newsletter to maintain relationships with former members, especially those in service. The first issue listed new fellows and former fellows who had enlisted or accepted a position elsewhere, as well as several letters and updates from members stationed in abroad. Subsequent issues contain updates on war efforts from Bacon and Hamor, death notices, and brief overviews of current research topics.

While only a handful of R.K.D. Club Bulletin issues were produced, it proved to be very popular to both current and fellow members. In a letter published in the March of 1919 R. K. D. Club Bulletin, Charles Howson of the 3rd Army A. E. F. wrote: 'To the Fellows of the Institute and the R. K. D. Club, Greetings: Today I have received the R. K. D. Club Bulletin, published under [the] date of February the first and it is difficult to express how much I appreciate hearing from the boys back at the ‘Tute.''

The known last issue of the R.K.D. Bulletin was published in November 1919, nearly a year after the close of the war. In 1937 the Robert Kennedy Duncan Club started a new publication, the Mellon Institute News, a far more ambitious weekly newsletter that was circulated to current and former fellows around the world for nearly four decades.

To learn more the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, check out previous posts on Scotty Tales, the university archives blog. And if you have any questions, don't hesitate to ask! Contact the University Archives at archives@andrew.cmu.edu or 412-268-5021.

by Emily Davis, Project Archivist, with scanning assistance from the CMU digitization lab