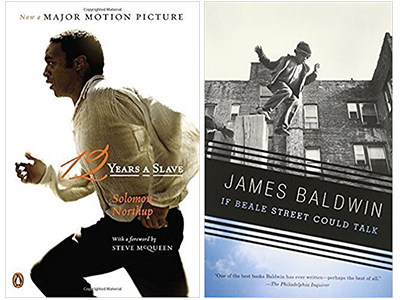

12 Years a Slave by Solomon Northup

In the inevitable debate, 'Which is better, the book or the movie?' it's good to remember that Chiwetel Ejiofor used Solomon Northup's book as 'the touchstone' to get into his character. 12 Years a Slave is immediate and heartbreaking even as the language is quaint to our modern ears. More telling for the times, though, was Northup's need to continually document his experience and to argue that slaves were not content and would have chosen freedom. Hopefully, these arguments would strike us today ironically as Huck Finn agonizing over his inability to think of blacks as inferior.

Solomon Northup, a free man, was lured to Washington, DC, drugged, and thrown into a pen with other enslaved men and women. He was beaten almost to death for resisting, and sold, all within sight of the U.S. Capitol Building. Even now, remnants of slave pens and slave quarters are being unearthed in cities.

My colleague Cindy Koller recently cataloged a book touching on this topic -- Slavery in the City: Architecture and Landscapes of Urban Slavery in North America – and I'm glad researchers are uncovering more about this part of our country's history.

Throughout his account, Northup looked for ways to escape. As he and the other captives were led in shackles to the boat that would literally 'sell them down the river,' Northup watched in despair as his opportunity passed by, while another man was rescued by white friends.

Sold to one master after another, Northup includes many exact descriptions of how slaves labored in swamps and cotton fields, how they were fed after the animals, on leftover corn and bacon fat, and how they slept for only a few hours, on boards. He includes details like his own sleeplessness from fear of not waking in time to get to the field; this lateness would bring a terrible beating. Working in punishing heat, with whippings so severe they shredded skin, Northup says 'Let not those who have never been placed in like circumstances, judge me harshly.'

Northup's book, and the movie, depict the horrors of children sold from mothers, masters raping enslaved women, and the torture and murder of enslaved people. For all the direct images on the screen, I felt the memoir showed me more of Solomon Northup's shock and suffering, as well as his determination to survive. And after pages of formal 19th century language, the occasional sharp exclamation of pain rings with even more effect.

Northup endures utter entrapment – forced to use another name, prevented by beatings from speaking about his true identity, unable to obtain paper and pen to write for help, or to mail a letter if he does. Bound to his master's plantation unless he has a pass, his every movement is limited, not only by his master but by every neighboring white person.

Whether the book or the film is 'better,' both are instrumental to our understanding. The fact that slavers extended their reach to kidnap hundreds of free African Americans in the pre-Civil War North was terrifying to me; that it took 12 years for Northup to get out, escaping so narrowly, shocked me. 12 Years a Slave reads like a suspense novel, but it is history – all the more terrifying for its truth.

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin

In a way, film led me to James Baldwin's work; the 2016 documentary 'I Am Not Your Negro' inspired me to pick up his essays. When I heard that Barry Jenkins, director of 'Moonlight,' recently began production on a film adaptation of If Beale Street Could Talk, I was inspired to read the 1974 novel.

The story is brief, and tender, and even though the slang distracted me a bit – 'cool cats,' 'getting the bread together' and 'digging each other' – Baldwin's prose has a musical flow, with touches of refreshing humor. Tish tells the story of falling in love with Fonny (Alonzo), introducing each other to their families and making plans for their future.

Their happiness is brief, though; as the novel begins, Tish is visiting Fonny in the horrific New York 'Tombs' where he struggles to maintain his hope and sanity. Tish is pregnant, trying to keep her job in spite of illness. She is also working with a young white lawyer to defend Fonny, who has been falsely accused of raping a Puerto Rican woman. Baldwin weaves flashbacks into the story with a rhythm that keeps us involved, hoping for the best, building our sympathy for the young lovers. We see the instant a white cop's pride is hurt and understand Fonny's arrest as revenge for that hurt. Overcrowded courts using plea bargains to move cases along, trapping poor people in a system of imprisonment and further poverty – these social critiques live and breathe in the characters of Beale Street.

One outstanding section follows Tish's mother to Puerto Rico where she tries to convince Fonny's accuser to take back her identification. How Baldwin made the agony of the wrongly-imprisoned man's mother equal to the rape victim's desperation I can't begin to describe. The scene is one I won't forget.

As a love story and coming-of-age story, If Beale Street Could Talk is magnificent; as a story of racial injustice, it's as current as a newspaper article. I'm looking forward to the 2018 release of the film.

by Jan Hardy, Cataloging Specialist